The Secret Curriculum - Hidden in Plain Sight

An Open Letter on Ireland's Curriculum Changes

Dear Reader,

What follows is an essay that initially began as a simple open letter on the upcoming changes to the curriculum. As I wrote however, the letter that I had planned grew into quite a lengthy essay. It became clear to me that it was a near impossible task to address my concerns without going into a substantial amount of detail. I hope that readers will bear with me, as this is a discussion that we cannot risk not having. This is not just a fight for our children, but a fight to maintain the very foundations of our society. It is imperative that we discuss and debate the overhaul of the curriculum openly, and reconsider the extent of the role that the schooling system should have in the lives of our children. The essay encompasses the following points, among others:

The role of Educators vs. Parents in shaping a child’s disposition and values.

The philosophy of critical pedagogy, its implications, and potential psychological impact on our children.

The appropriateness of including gender identity and Queer Theory within the curriculum, and how that is in direct contradiction to the curriculum’s stated position on identity formation.

The use of Social and Emotional Learning, the CASEL framework, and its supporting evidence (or not).

I want an education for my children that is balanced, neutral, and that focuses on ensuring that they are well educated and well-equipped for their futures. I want parents to be well informed about the content of the curriculum, for their concerns to be taken seriously and for clear policies to be made available for inspection by parents. I want teachers to be supported to teach within the confines of their own professional competencies and knowledge base, and not forced teach outside of that.

Throughout the essay, questions are asked of parents and are intended to serve as prompts for further consideration and discussion. For ease of access and so that parents can return to these questions if needed, a list of these can be found at the end of the essay.

Yours sincerely,

A concerned mother

I write this essay in response to the proposed changes to the SPHE/RSE1 curriculum. However recently, it has become apparent to me that the concepts I will discuss here are also in the process of being embedded into almost every subject within both the primary and post-primary curriculum, therefore my concerns are not restricted to SPHE/RSE. I write this both as a concerned mother and as someone with an educational background in psychology, who feels that the new curriculum has the potential to be detrimental, as opposed to promoting wellbeing and positive mental health as has been suggested. This essay is directed at those within the NCCA2 and government more broadly who are responsible for the changes to the curriculum, as well as being directed at parents and teachers. It is my hope that by publishing this, it may open the door to a more honest discussion about the true content of the curriculum and whether it has any place within Irish society.

The Junior Cycle draft document states plainly that it intends to shape our children’s ‘dispositions and values’. In other words, it intends to shape our children’s mental and emotional outlook, their attitudes, and their worldview. Firstly, we should question whether this is the role of educators or whether this responsibility should lie primarily with a child’s parents and family. If it is indeed the role of schools, then we should at the very least ensure that we, as parents, have a clear understanding of what those values are and whether they align with our own before allowing them to be imposed upon our children. I encourage every parent to thoroughly research the academic literature undergirding the curriculum and to consider whether they feel that the viewpoints expressed in these texts are consistent with their own values and those that they wish to pass onto their children. The Department of Education does not have the right to override a parent’s conscience on these matters. Further, they have a responsibility to be transparent about the content of the curriculum and to take seriously the concerns and questions expressed by parents, neither of which the Department is currently doing.

I will be very blunt; the proposed curriculum is a Trojan Horse and not at all what it purports to be. It is the indoctrination of our children in socio-political ideology masquerading as instruction in psychosocial wellbeing. Presented as being under the umbrella of the new ‘wellbeing programme’, one would assume that its ultimate aim is to improve student’s individual wellbeing. It is hard to object to assertions of nurturing ‘self-awareness and positive self-worth’ or to helping students to develop and maintain ‘respectful and caring relationships’, as is suggested by the aims outlined in the draft document. However, the NCCA has cleverly shrouded the true intentions of the curriculum in this seemingly inoffensive language, disguising the ideology which, nevertheless, is apparent if you are discerning enough to parse out those words and phrases that read as glaring red flags. I can only guess that this was done intentionally in the hopes that most parents would not see past the psychological buzzwords and assume the best intentions for their children. Most obvious of these red flags is the acknowledgment in paragraph five of the Rationale section to the use of critical pedagogy and to the confirmation, which was interestingly hidden away in the appendices, that the social and emotional learning (SEL) outlined in this programme refers to that set out by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) Framework. Neither critical pedagogy nor the CASEL framework should be things we want anywhere near our children’s education.

Critical pedagogy is an explicitly political teaching philosophy, and is arguably, a type of thought-reform which encourages students to adopt a specific conflict-oriented worldview. For this reason, I do not consent to this being taught to my children and I hope that by the end of this letter many more parents will feel compelled to voice their opposition as well. To parents and teachers, I ask you to be alert to the fact that the language used in the draft document (and related materials) functions to appeal to your good nature and to hijack your empathy. Further, this use of language makes it very difficult to object to the contents without appearing unreasonable. However, once you understand the origins of the pedagogy and theory which form the basis for these curriculum changes it becomes entirely reasonable to object. I believe teachers can sense that something is amiss with the curriculum changes which has led to a gradual dumbing down of the curriculum and a deemphasis of core knowledge. Just as students and parents are being railroaded into these changes, so too are teachers.

I will begin this essay by first discussing what exactly I mean when I state that this programme is indoctrination in socio-political ideology and describe the principles of critical pedagogy. This is because many may not be familiar with specific concepts or the ideological basis of some of the terminology used in the draft document. I hope that by highlighting some of this terminology it will also help parents to recognise potential ideology within guidance documentation for teachers and within educational material that their children receive at school, allowing them to push back where necessary. I will also discuss the potential psychological consequences of the universal implementation of this so-called wellbeing programme on our youth. Finally, I will outline some of the issues that I have with the programme itself as a psychosocial intervention and the suggested evidence base for CASEL’s SEL framework, as I do not believe that we have adequate and reliable evidence to support its widespread adoption at this time.

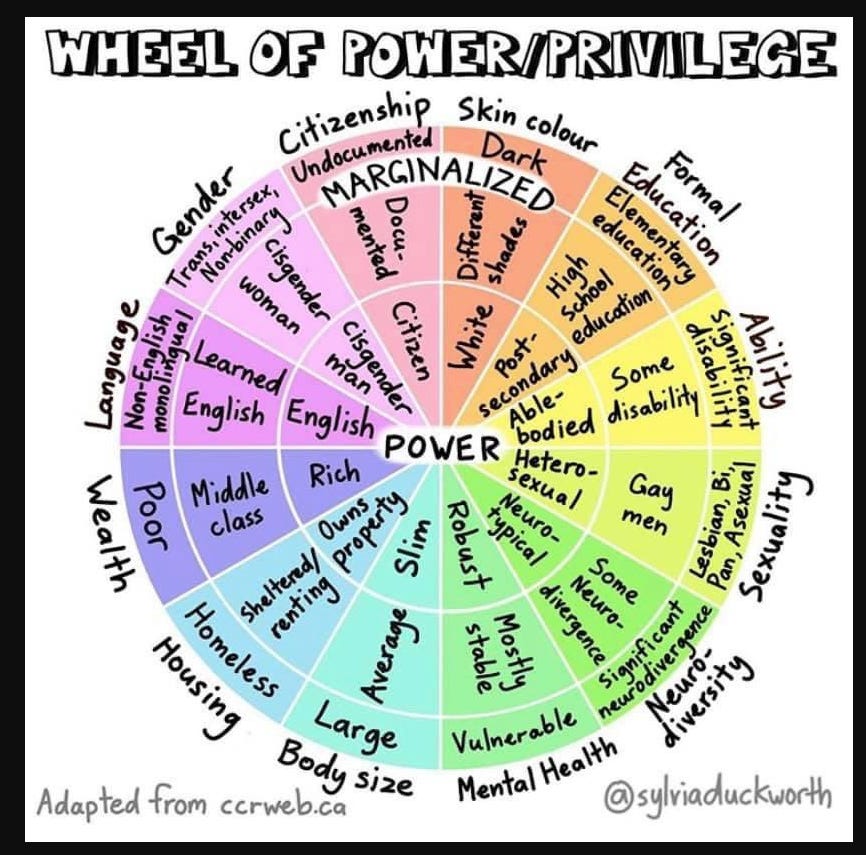

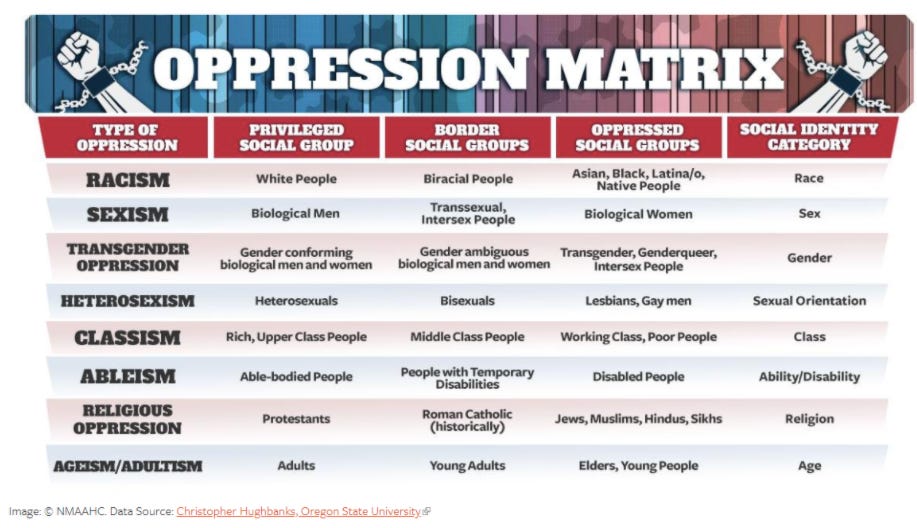

Critical Pedagogy

Critical pedagogy3 is a teaching philosophy grounded in Critical Theory that teaches Critical Social Justice activism and serves to remake society. Those that subscribe to Critical Theory’s conceptualisation of the world, understand and interpret reality in a fundamentally different manner than the rest of us. For them, anything and everything that exists within society and culture must be viewed as an imbalance of power and privilege between different groups which, in turn produces inequality and oppression. Society then, is characterised by ongoing struggles and conflicts between these groups. There are many different applications of Critical Theory which divide people (and thus power) based on specific identity-based categorisations. For instance, in relation to race, gender and sexuality, or class. Efforts to rectify power imbalances through the application of Critical Theory fall within the realm of Critical Social Justice activism, which advocates for the redistribution of privilege and power. Far from progressing society as one might assume, Critical Social Justice is destructive and regressive as it reduces each complex individual down to an over-simplistic categorisation of persons based on immutable characteristics. By its very nature, it fosters divisiveness. Its increasing hold on western society is leading to widespread destabilisation, both on the individual and societal level. It’s important to note that the present-day use of the term ‘social justice’ is typically referring to Critical Social Justice, and not referencing the fundamental liberal aim of correcting social inequalities as in how the term has been historically used4. To be clear, I am not opposed to social justice which aims to ensure equality of access and opportunity for all. I will now expand further on critical pedagogy and its implications.

Firstly, it is necessary to point out that many words have entirely separate and very specific meanings when used by Critical Theorists. For this reason, we must be careful when reading the draft document and supporting materials to ensure that we are aware of these alternate meanings so that we can truly understand what is being proposed. For instance, and most importantly, the word critical, as used by those that employ critical teaching practices, is not referring to the common usage of the word – a careful or skilful analysis of the faults or merits of a given argument such as when we refer to employing critical thinking or critical analysis5. Rather, they are referring to engaging in a form of social critique aimed at revealing, challenging, and dismantling structures or systems of power and oppression within society.

The draft document is peppered with references to students developing a critical understanding. For instance, in Figure 1 under the subsection key skills in relation to literacy, the document states that students will learn to read ‘for enjoyment and with critical understanding’. This is not normal literacy, but rather critical literacy, which refers to reading and interpreting text in a very specific manner6. Students are taught to focus on socio-political issues and to examine a given text in order to create problems with it that relate to issues of power, oppression, and social justice. The aim is to agitate students into activism around those issues. With this in mind, we can see that the intention here is not to teach students to critically evaluate the literature by engaging in a nuanced and balanced appraisal of the text. If it were, I would have no opposition given that the capacity for true critical analysis is a crucial skill for academic success and informed decision-making across many life domains. Neither is a text read to gain established knowledge or to appreciate it as an important literary piece.

The outcome of critical pedagogy’s approach to literacy is that students are no longer able to read with objectivity as everything is deemed problematic and students are encouraged to allow their resultant feelings of indignation to take precedence over their learning. In recent years we have seen that this often leads to classic novels being labelled problematic and compromising student’s feelings of safety, resulting in efforts to have these novels removed from the curriculum or edited. For instance, it was recently announced that new editions of Roald Dahl books would be edited to remove any language or descriptions that may cause offense, such as references to ‘fat’ or ‘boys and girls’. Alternatively, To Kill a Mocking Bird by Harper Lee was recently criticised here in Ireland for its depiction of racism despite the fact that the very purpose of the novel was to illustrate and challenge systemic racism which operated within the American justice system and society more broadly during the 1930’s. Through a critical lens however, it is argued that the fact that Harper Lee was a white woman writing about racism somehow invalidates the great lessons that she wrote about in her book, which led to calls to have the novel removed from the curriculum to prevent ‘upset’. An example of the proverbial throwing the baby out with the bath water. But this is what happens when critical pedagogy is used in the classroom – actual learning is forgone in favour of political activism and opportunities to build psychological resilience in response to difficult topics are undermined.

I find it disingenuous that the Junior Cycle draft document was not more explicit about the principles of critical pedagogy, about its radical origins, or about the motives of those that use its methods and practices. How can parents consent to the curriculum changes if they are not informed of exactly what this philosophy is and the implications of its uses in the classroom? The most crucial thing for parents to understand is that critical educators view teaching as a political act and believe that teaching can never be politically neutral7. The end goal is the redistribution of wealth, land, resources, privilege, opportunities, and power in order to achieve equity, which in turn brings about social justice. Critical educators believe that the purpose of education is not to educate their students by simply imparting knowledge to them, such as in the traditional educational model. They believe that traditional forms of knowledge are constructed by those in power, for the purpose of maintaining power rather than about the genuine pursuit of objective truth. They argue that traditional educational practices legitimise dominant and oppressive ideologies, knowledge, and social formations, and therefore reinforce and maintain the status quo.

What is the status quo to which they are referring? That is the European descent, middle class, English speaking, heterosexual, Christian, able-bodied, and assumed male perspective and position. Membership to any one of these groups earns you the label of oppressor, unless you engage in ‘doing the work’ in perpetuity. To any parent reading this, I ask you to consider how many of these groups does your child fall into? Are you comfortable with your child being taught to feel shame and guilt for their race, sexuality, religion, family culture, socioeconomic status etc? Are you comfortable with your child being led to believe that if they can be categorised into any one or more of these groups then they are oppressive simply by virtue of their unintentional membership? Because this is exactly what critical educators intend for our children to be taught. If you don’t think this will lead to a sharp uptick in depression and anxiety among our youth, you do not understand the mental health impacts of chronically being made to feel shame simply for existing as you are. I would like to point out that instilling shame is a tactic often used by psychological abusers to control and manipulate their victims. No one should ever be made to feel that there is something inherently wrong with them, certainly not a child, and to do so is incredibly psychologically harmful. Consequently, any teacher that deliberately engages in practices within the classroom that divide and penalize students based on identity group is in my estimation, guilty of emotional abuse.

Critical educators claim that a teacher must either take a ‘critical stance’ toward teaching in which they are always working towards revolutionary transformation of society and culture, otherwise they are teaching in service of the current status quo and the oppression of the marginalised within society. It is a very black and white mentality; you are either with us (the oppressed) or against us (the oppressor). There is a concerted agenda by those that intentionally engage in critical teaching practices to indoctrinate children into adopting this same socio-political ideology and to create activists, or as they call them ‘change agents’. If Irish teachers do not agree with this, I implore you to push back against the explicit inclusion of critical pedagogy in the curriculum specification.

Critical pedagogy originated from the musings of the Brazilian educator Paulo Freire, who penned the seminal text in critical pedagogy, Pedagogy of the Oppressed8 and his later book, The Politics of Education9. Freire was influenced by the writings of G.W.F. Hegel and Karl Marx, as well as other Neo-Marxist philosophers such as Herbert Marcuse and Antonio Gramsci. In his writings, Freire cited the methods of tyrannical leaders such Mao Zedong, Vladimir Lenin, and Fidel Castro. In fact, despite Mao’s methods leading to the deaths of millions of people, his cultural revolution was lauded by Freire as ‘the most genial solution of the century’10. He compared Mao’s brainwashing of the Chinese people and weaponization of the youth favourably to Stalin, who was unable to overcome his people’s resistance and solved the problem by simply shooting the peasants. These are radical ideas, indeed.

Freire’s concepts were further developed by scholars such as Henry Giroux, Michael Apple, Peter McLaren, and Gloria Ladson-Billings, to name a few. There is no denying that critical educational practices have a foundation in Marxist thought, in addition to poststructuralism and postmodernism. These scholars are self-proclaimed ‘critical Marxists’11. The same concepts that Marx applied to understanding society’s economic and material conditions are instead applied to identity and culture. My question to parents is, do you send your children to school so that they can be brainwashed into adopting a Neo-Marxist understanding of society and humanity? Is this truly the worldview that you wish for them to hold? My question to the Department of Education is, why are you concerned with injecting ideology into our schools? Are you or are you not foisting this Neo-Marxist ideology upon our children with the aim of influencing their ‘dispositions and values’ so that they are in alignment with such? Whatever the flaws of current society, the concepts laid out by Karl Marx’s economic and cultural philosophy have led to the deaths of more than 100 million people in various communist regimes over the last century. Marxism has never worked, and no variation or adaptation of its ideas will ever work. While it may be sold as a path to utopia where liberation and collectivism prevail, the hard truth is that it always slides into tyranny, and it is high time that we abandon these concepts entirely. We certainly should not be fusing them into our curriculum.

Oppression, according to Critical Theorists, is pervasive and always present. The question for them is not whether oppression exists within a given context, it is assumed to be inherent to all of society and culture. Therefore, their goal is to reveal its many different manifestations so that one is able to challenge these proposed systemic inequalities. What is concerning however, is that whether or not a person is categorised into a dominant and oppressive group seems to be largely dependent on external and unchangeable characteristics such as the colour of a person's skin or their sex, rather than on whether or not they actually engage in abusive and oppressive behaviours or hold prejudiced beliefs. At the same time, actual prejudiced beliefs or violent behaviour perpetrated against members of a ‘dominant’ group by a ‘marginalised’ group is excused as justifiable and considered restitution for past injustices12.

What does it look like when these ideas are applied in the educational setting13? Your children’s education will be structured in such a way that frames your sons as privileged misogynists simply because they are male. Your heterosexual daughter will be led to believe that while she may be oppressed because she is female, she herself is also privileged and therefore oppressive because she is ‘cis-heteronormative’ or white. Your white child will be accused of ‘white fragility’14 if she insists that she is not racist simply because of the colour of her skin and asked to examine her ‘whiteness’15. Your children will not be judged based on the content of their character. Rather, they will be led to believe that they are inherently racists if their skin colour is white, misogynistic or toxic if they are male, homophobic or transphobic if they are ‘heteronormative’ or ‘cisgender’, ableist if they have no disability, a perpetuator of intolerance, patriarchy, and colonialism if they are of a Christian faith. They will be taught that gender is a spectrum and compelled to declare their pronouns as an exercise in demonstrating their allyship. These are all different manifestations of the current applications of Critical Theory. They will be told that if they question such propositions, they are an intolerant person and they will be shamed into silence.

Yet this is all just bigotry under a different guise. There is no such thing as positive discrimination. Discrimination is discrimination no matter whether it is aimed at the minority or the majority and it is always wrong. These prejudiced views are already being taught to children within schools that have adopted these teaching practices all across the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and elsewhere. Are we prepared to let this happen here in Ireland? The further injection of Critical Theory into the Irish education system via the proposed SPHE curriculum is the thin end of the wedge. It may initially seem innocent and inclusive, but as we have already seen occur elsewhere, we will begin to see more and more radical applications of Critical Theory within our schools in the years following its introduction into SPHE. And as a result, we will see a decline in academic achievement and an increase in mental health problems among our youth. This can already be observed in the United States where their education system has been geared toward this type of teaching for some time. Rather than seeing a decline in mental health problems among their youth and improved coping as one would expect from the widespread incorporation of social and emotional learning into their curriculum, unprecedented levels of depression, anxiety, and suicidality are occurring.

The notion that everything that exists within society should be viewed through the lens of the abuse and imbalance of power is, in my opinion, a profoundly reductive and pessimistic worldview. It is certainly not one that I wish for my children to hold. I am positive that I am not alone in this and would suggest that the proportion of parents and teachers that disagree with the propositions of Critical Theory make up the silent majority. However, the NCCA’s attempt to present the new curriculum in a favourable light while obfuscating the underlying ideology prevents them from realising their opposition or from expressing their dissent. I absolutely am not arguing that there does not exist instances of abuse of power, discrimination, or oppression within society. Nor am I suggesting that we should not counteract such instances when they become apparent. However, the suggestion that all existing structures, group relations, institutions, cultural norms, and knowledge of the workings of the world is predicated on power and oppression is absurd. I would go so far as to call it a delusion of persecution. It absolutely is not a rational argument and entirely ignores the myriad of motivators of human behaviour that exist apart from the pursuit of power. To teach our children to view the world in this way through critical pedagogy is emotionally destabilising and ingrains in them an external locus of control, while at the same time presenting them with a ready-made solution to the discomfort, shame, and cognitive dissonance they will experience – become radicalised Social Justice activists. This is not what I want for my children. And this should not be the purpose of public education.

Awareness, Dialogue, ‘Reflection & Action’

So, how is it that critical pedagogy works to shape our children in service of radical social and political transformation? To refer back to the draft document, page 11 describes three elements (awareness, dialogue, ‘reflection and action’) which are proposed to support effective teaching and learning in SPHE. Anyone familiar with Freire’s work will instantly recognise that these three elements are synonymous with what Freire referred to as conscientization, dialogue, and praxis, which form the bedrock of critical pedagogy. Awareness or conscientization is the process by which students reflect on their experiences and develop awareness of how those experiences are shaped by what critical educators believe, is a fundamentally oppressive society, as well as developing the capacity to act in opposition to this proposed oppression. When a person has developed this capacity, they are considered to have critical consciousness, otherwise known colloquially as, ‘woke’. Essentially, it is like putting on a pair of rose-tinted glasses, except instead of mistakenly seeing everything in an overly positive light, our children will see everything in an overly pessimistic and disempowering light. It teaches them to view themselves as victims and also provides them with a group to blame for their victimization, robbing them of the capacity for self-determination. The resultant feelings of victimization or alternatively, the shame that arises from seeing oneself as a member of an oppressive group are then used as emotional levers which can be utilised to agitate students into political activism. Prevailing social norms or anything that can be categorised as ‘normative’ ways of being are considered problematic and regarded with disdain within this worldview.

In this way, students will be taught to alter their worldview and question the very terms of society as it currently exists. You can be certain that we will begin to see the incremental and sustained erosion of Irish culture in the years to follow. The document states that students must develop awareness of how their sense of self and how they live their lives is influenced by culture, important others, and social norms. But what the document does not clearly articulate is exactly what influences will be framed negatively and what alternate norms they intend to instil in our youth. However, given that the curriculum, by its own admission, is grounded in critical pedagogy and I have just explained exactly what the principles of this philosophy are, we can easily deduce what our children will actually be taught to believe.

Dialogue is a practice in which discussion is used to interrogate the students' values, assumptions, and experiences with the aim of uncovering alleged biases. However, make no mistake, this is not true discussion nor are they uncovering actual biases in most instances. Diversity of opinion and open discussion are never tolerated in these sessions. Students will be coerced into adopting a particular viewpoint which aligns with the narrative of the oppressed. Everything apart from the permitted viewpoint will be framed as a bias which supports the oppression of the marginalised and vocalisations of those views will be pointed to as examples of one or the other –ism or –phobia, fostering shame in those that dare to speak up. If you are a student that can be categorised into one of the ‘oppressor’ groups, you have limited options for how you can respond to these discussions without being accused of sexism, racism, transphobia etc. The only permissible response is acquiescence and allyship. For members of ‘oppressed’ groups who refuse to see themselves as victims who are at the mercy of an oppressive society, they are often admonished for having ‘internalised’ their oppression.

Given that this dialogue occurs within the adolescents’ peer group, and because this age group places so much importance on the opinions of their peers, students who are subjected to this practice are likely to feel pressure to self-censor and to conform to the prevailing opinion within the group out of fear of ostracization. They may even take on the identity of an oppressed group, for instance in relation to gender identity, to escape the social and psychological pressure that is created from these types of conditions. The purpose of dialogue is to agitate students into action by creating an intensely emotionally charged response to these identity-based topics, whereby leading students to feel compelled to act on those emotions. As Freire described it, dialogue is the essence of revolutionary action.

A Villanova (USA) professor’s account of how these concepts went awry in an educational programme with a group of adolescents. Vincent Lloyd’s full article can be found here.

Reflection and action (or praxis) is where students are expected to act on their new consciousness out in the world. Notice that in the footnote defining reflection (p. 11), it does not refer to the standard use of the word, which means to give serious thought or consideration to a topic. It defines reflection as the ability to take a ‘critical stance’ before deciding and acting. I take no issue with attempts to help my children develop the capacity for true reflection. However, the form of reflection they are referring to here teaches our youth to interpret everything through the lens of race, class, and gender-based power relations before forming an opinion or acting on it. I would argue that this practice is instilling in our youth the tendency to engage in a kind of cognitive distortion. Similar to all-or-nothing thinking, our youth are being taught to think of everything in absolute terms – anything and everything must be viewed as a polarisation of power between oppressive and oppressed groups. There is no nuance and there is no grey area. It is suggested that these practices remove bias, but the actual fact is that they simply re-programme our youth into a new set of biases. Thinking in absolute terms is a very unhealthy thinking style which promotes emotional distress and compromises a person’s ability to effectively respond to life's challenges. We should not be promoting this type of thinking in our youth as it is associated with increased levels of depression, anxiety, and relationship instability. In taking action, students are encouraged to bring their new awareness back to their families, communities, and society at large in order to bring about revolutionary change. Over the last few years, we have seen this play out in the form of the tearing down of statues, violent rioting, defacing famous artwork, and forcing universities to cancel certain speakers on campuses.

Evergreen State University, USA - Another example the outcomes of critical theory in an educational institution.

Gender Identity and Queer Theory

Gender identity warrants particular attention here given that it holds such prominence within the new curriculum. The Provision of Objective Sex Education Bill 2018 states that students are guaranteed the right to receive factual, objective, and age-appropriate relationships and sexuality education. The concepts that the new curriculum intends to teach in relation to gender identity are neither factual, objective, or neutral. They are based on ideology, not science. They have emerged out of the field of Queer Theory, which is an application of Critical Theory focusing specifically on critiquing society’s definitions of gender and sexuality. In reaction to what they suggest is oppressive cis-heteronormativity, Queer Theory seeks to blur the boundaries between and definitions of sexual and gender-based identity categories. Queer Theory is an inherently political field of study, and therefore education deriving from it cannot be considered neutral.

Assertions that each person has a gender identity which is entirely socially constructed and independent of biological sex, and that gender is fluid or a spectrum are highly conjectural. Research on the neurobiology of gender identity is limited, and that which does exist is inconsistent and inconclusive. For this reason, gender identity should not be taught in schools as though it were an indisputable fact. Sexual education for adolescents should be taught from the biological perspective, as well as the psychological perspective in order to address the cognitive and emotional aspects of sexual maturation, sexual readiness, relationships, and risky sexual behaviour. However, there is absolutely no justification for teaching sexual education from the Critical/Queer perspective.

I find it incredibly alarming that those that argue for the teaching of sexuality from the perspective of Queer Theory show a complete rejection of the developmental neuroscience and psychological evidence that children and adolescents are not miniature adults and should not be treated as such16. There is an intense effort to introduce this ideology to adolescents, as well as very young children, despite the fact that they are not developmentally able to make sense of these concepts nor their implications. We do not expose children or adolescents to developmentally inappropriate sexual content or concepts so as to safeguard them from potential psychological harm or exploitation by predatory adults.

I find it stomach churning that within queer theory there is an ongoing attack on the concept of childhood innocence and the (reasonable and appropriate) societal view of children as non-sexual beings. These scholars claim that the concept of childhood innocence is entirely socially constructed, and its existence serves only to constrict children’s sexual exploration. Despite this being an alarming position to hold, the NCCA consulted with supporters of this perspective in the development of the new RSE curriculum. Aoife Neary is a lecturer from University of Limerick whose research focuses on the politics of gender and sexuality from the perspective of Queer Theory. She has helped in the development of an e-resource on gender identity and expression to be used by second-level schools and has developed several videos relating to LGBTQI+ content which are hosted on the Curriculum Online SPHE toolkit. In agreement with other Queer Theory scholars, she states in one of her academic papers that ‘the trope of the innocent child regulates and constrains what children may learn about sexuality’17. Further, in a statement made to the Oireachtas during the review of RSE, she proposed:

We must take account of how fears around ‘childhood innocence’ act as a barrier in ways that don’t account for the capabilities of children or the wants of parents. To be effective, comprehensive RSE must begin in early years – from as young as three – in partnership with parents.

But childhood innocence is not a trope, and it is not a social construct. We consider children innocent because they are psychologically and experientially innocent. This innocence is what sharply demarcates the boundaries between childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. If we allow the boundaries between these categories to be blurred as proponents of Queer Theory argue for, what then can be assumed about what behaviours are deemed appropriate within relationships between individuals in these different age groups? I disagree with Aoife Neary in relation to her statement about the ‘wants of parents’. I believe if you properly consulted parents in an unbiased and open manner, you would find that most would strongly object to the claim that there is no such thing as childhood innocence and have no desire to have their toddlers taught about gender ideology or sexuality within schools. If we allow this into the Junior Cycle, we open the door to allowing this to be taught to our children as young as three, long before children are able to grasp these concepts.

You will not steal my children’s innocence. You will not place them in harm’s way by exposing them to concepts that make it easier for them to be preyed upon by those with malevolent intent. I want parents to be aware that governmental representatives are actively discussing how they can override the wishes of a parent to opt out of this so-called education by attempting to frame comprehensive sexuality education as a child’s human right that supersedes the Constitutional rights of parents in relation to their children’s education (see the Oireachtas meeting held on the 14th July 2022 and the recently published report on the consultation on the SPHE curriculum).

While I am in agreement with the draft document’s conceptualisation of adolescent identity formation given that it is consistent with what we know from the field of developmental psychology, I would like to point out that the contents of the curriculum are incompatible with this stated position. The document states:

Adolescence is a time of important change and challenge for young people as they come to a clearer sense of their identity and gain a more secure sense of who they are. This process of ‘becoming your own person’ and gaining a secure sense of identity is a life-long process. In adolescence it’s a prime developmental concern. (p. 2)

It is true that adolescence is a transitional period from childhood to adulthood, a key feature of which is identity exploration and formation. The development of a consistent and cohesive understanding of oneself during this period is crucial for healthy psychosocial development and subsequent success across the lifespan. What I cannot understand then, is why the curriculum is drawing from Queer Theory in the teaching of gender identity, which is in direct contradiction to the idea of promoting the achievement of a consistent and cohesive identity. As Queer Theorist Hannah Dyer states, ‘queerness is that which undoes identity, not what holds it together’18. We are confusing adolescents and undermining their capacity to achieve identity coherence and consistency when we teach them that their identity is fluid and teach them to resist anything that is considered normal categorisation in relation to sexuality and gender. I would like the NCCA to explain their rationale for amending the curriculum so that it has a grounding in Queer Theory rather than empirical evidence about adolescent development and human sexuality. I would also like them to explain how they reconcile what has been written in the draft document with regards to adolescent identity formation with their adoption of Queer Theory within the curriculum – two perspectives which are mutually exclusive.

I take issue with the use of the terms heteronormativity and cisnormativity within the curriculum, which are often used as pejorative terms among those that subscribe to the beliefs of Queer Theory. What is implied is that to be ‘normal’ is somehow an undesirable way to be, as this is viewed as conforming to an oppressive norm. This negative connotation coupled with certain typical psychosocial processes could create the ideal conditions for trans identity to spread like a social contagion through peer groups or within schools. Adolescents derive their self-concept and esteem largely from the opinions of their peers19 and are highly motivated by a desire to feel included and accepted by their peer group. In addition, adolescents feel the effects of social isolation or ostracization more acutely than younger children or adults. Consequently, peer norms are a significant driver of adolescent decision-making and behaviour20. It is not unusual for adolescents to adjust their behaviour and views so that they are in alignment with those of their peers. Even behaviours which are considered risky may be easily adopted if they are perceived as having high social value among their peer group21. An adolescent may view the potential social benefits gained by engaging in risky behaviours as outweighing any potential future negative consequences, partly because their capacity for long-term planning is underdeveloped.

Currently, to identify as some form of gender nonconforming is given very high social value among adolescent peer groups and society more broadly, and there are many social benefits that are conferred by identifying as such. Consider the validation, affirmation, and celebrity status that many popular trans TikTok stars currently receive, and as a result the scores of young people that try to emulate this online behaviour. As such, one probable explanation for why some adolescents are identifying as trans is that they are doing so because it is currently being perceived as having high social value and they are particularly susceptible to social influence while also being highly sensitive to social exclusion. For the majority, it is plausibly not unlike any other fad that adolescents would have adopted in the past except this one can have very serious life-long consequences because of the ‘affirmative’ approach that drives them towards medication and surgery.

It is not just that these concepts in relation to gender identity are not factual, but I believe that they have the potential to be dangerous when they are taught indiscriminately to all students. It is developmentally appropriate for identity exploration during adolescence to involve some degree of confusion. However, a persistently and markedly unstable self-image or sense of self is characteristic of identity pathology. Instability or fluidity in a person’s sense of self can feel incredibly painful and chaotic for those that experience it and therefore it would be inadvisable to encourage such instability. Biological vulnerabilities and risky environmental contexts may make a person more susceptible to the development of identity disturbances. Yet teachers are not, in most instances, going to be aware of each adolescent's unique history and so will not know, nor are they equipped to assess, whether they have an adolescent with a heightened risk for identity disturbance within their group. Consequently, harm can be unwittingly done to these already at-risk individuals by promoting confusion around their gender identity and presenting social or medical transitioning as a ready-made solution to their identity-related distress. In addition, adolescents that may have never had a susceptibility are being misled to believe that they need to do something in response to what is more than likely just normal levels of adolescent identity confusion that often resolve in time without intervention as an adolescent matures.

Normal identity development is being disrupted by the bombardment of this ideology on television, social media, and now within schools. I wonder who will be held liable for any psychological harm that may occur as a result of teaching in these topics? Further, I would also like to know whether teachers will be advised to affirm students’ gender identities without consent from or conferring with parents, as is regularly being practiced in the UK and the US?

There seems to be an unwarranted focus on trans activism and affirming gender identities within the SPHE toolkit, which I find to be a cause for concern. The curriculum seems to have been largely advised by trans activists rather than being informed by the medical and psychological evidence base. As such, there is a biased presentation of information on trans issues that focuses solely on promoting and affirming transitioning while excluding open discussion about the potential negative consequences. Social and medical transitioning are not benign interventions. There are many ramifications to transitioning in childhood or adolescents. As such, if we feel it necessary to educate students on trans issues within schools then this education should be balanced and include honest discussion about the long-term health consequences of puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and surgery, as well as the lived experiences of de-transitioners and those that go on to experience regret. Further, transitioning should not be presented as a cure for mental health difficulties and identity related distress given that for many, these issues persist post-transition. The fact that this is the case, challenges the presupposition that the mental health difficulties that are experienced by many trans youths are caused by the incongruence between their physical body and gender identity. The reality is that we do not know the direction of the association between mental health difficulties and trans identity. Perpetuating confusion about correlation and causation within the discourse around trans youth’s mental health is not helpful and places them at risk of not receiving the care they deserve.

Most importantly, there is no possible way that an adolescent can provide informed consent for these procedures given their relative neuropsychological underdevelopment, and therefore we should be cautious about how we approach discussing these topics with them. Adolescent brains are still developing and they are undergoing extensive changes in brain regions associated with the capacity to evaluate risk and reward which inform decision-making, emotional regulation and long-term planning22. Consequently, adolescence is marked by a sense of invulnerability, impulsivity, and a limited capacity to fully grasp potential long-term consequences for their choices and behaviours. This is why it is important that adolescents are communicated clear expectations and given firm and consistent boundaries by parents and other important adults during this developmental period. As parents and adults, we are tasked with the responsibility of giving our adolescents enough freedom to explore and grow within the boundaries of their capabilities, while at the same time still taking charge of decisions which are beyond their ability to comprehend, particularly those with lifelong consequences. With all of this in mind and given the significant gaps in the research and evidence base, it seems reckless to have teachers take an affirmative approach and educate students on these issues within an uncontrolled environment without due caution or concern for potential harms that may result. Particularly in light of the publication of the Cass Review interim report of the Tavistock gender clinic, which should be prompting us to reconsider our approach to helping gender nonconforming children given its findings.

Social and Emotional Learning

Finally, I would like to discuss the inclusion of CASEL’s SEL framework within the curriculum and whether its proposed benefits are supported by evidence. CASEL’s framework encourages students to develop a variety of social and emotional skills that fall within five broad competency areas. These are - self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision making. In and of itself, this is a reasonable goal. However, I would like to emphasize that I strongly oppose the use of SEL as a vehicle for the delivery of instruction in Critical Social Justice. It is clear that NCCA intends for SEL to be used in this fashion given that the draft document indicates that the competencies will be taught through critical pedagogy, as I have outlined above. This also appears to be the intention of CASEL given recent publications from the organisation which outline their shift to a Transformative (Justice-Oriented) form of SEL that largely prioritises using SEL as a means to rectify racial/ethnic inequities rather than the previous aim of promoting personal responsibility and character development23. This new form of SEL elaborates on the definitions of its five competencies to include aspects that are not in the initial definitions and that would not be rationally inferred. For example, self-management was initially defined as the ability to regulate one’s emotions, thoughts and behaviours in different situations. However, in a recent publication by CASEL, this competency now includes developing resiliency and expressing agency through resisting injustices and practicing anti-racism. As you can see, the competencies are now filtered through Critical Theory and aim to impart to student’s a critical consciousness of race. Critical Theory is like a fatal mind virus, and whatever benefits may be gained from an intervention based on appropriate psychological theory will be undermined by the incorporation of Critical Theory into its SEL instruction. The NCCA should clarify how they are defining the five competencies and confirm whether or not the curriculum will be based on Transformative SEL or the older forms of SEL.

I have serious questions regarding the evidence put forward by CASEL with regards to their framework. SEL is now a multi-billion-dollar industry, and as such there is certainly an incentive to present it as a panacea for all child/adolescent personal, social, and academic issues. I would argue however, that the benefits of SEL have been wildly overstated. In fact, given that CASEL’s framework has morphed from a personal responsibility model (based on psychological theory) to a justice-oriented model (based on Critical Theory) since its inception, one could argue that older studies cannot and should not be used by CASEL to bolster their claims that SEL, in its current form, is effective in producing the variety of positive outcomes that are claimed to be associated with it. The bulk of CASEL’s claims of positive outcomes derive from a meta-analysis conducted by Durlak and colleagues24 which included 213 school-based SEL interventions involving students from kindergarten through high school during the period of 1955 to 2007. Following criticisms on the lack of evidence to suggest whether improvements are sustained long-term, a further meta-analysis of follow-up effects was conducted by Taylor and colleagues25 and included studies published between 1981 and 2014. Transformative SEL however, only came into conception in 201926, and since then there has been a significant shift in how the competencies are defined and the proposed content of programmes. How these skills are defined is important because without proper and consistent operationalisation and measurement, we cannot systematically collect data, observe patterns, and draw causal inferences between SEL interventions and student outcomes.

There may indeed be merit to the claim that improving student’s social and emotional skills will contribute to more positive academic and life outcomes, particularly in situations where there are serious deficits. However, one cannot infer from the available evidence that CASEL’s particular brand of SEL is effective in producing the same. Proponents of CASEL seem to be conflating these two statements. Any study which sought to develop at least one social and emotional skill was eligible for inclusion in the aforementioned meta-analyses. These meta-analyses are not evaluations of interventions which implemented CASEL’s framework and its five competencies, certainly not in its present form. Both combined the different types of skills (cognitive, affective, and social) into a single outcome variable rather than assessing them according to their relevance to each of the five competency areas. These skills were assessed via interviews, role play, or student self-report questionnaires. Inherent in this type of measurement is the risk that participants will provide answers that they feel are desirable, but not an accurate representation of their own beliefs or motivations27. This may be particularly true for younger populations who may alter their responses so that they align with those of their peers or to align with the perceived expectations of their teachers. This begs the question, are students actually cultivating these competencies or are they simply telling teachers what they believe they want to hear? And are these new skills reflected in the behaviours they engage in? The research suggests that in fact, positive effects observed in relation to prosocial behaviour and conduct problems are not sustained at 6 months or more post intervention28. Further, reductions in symptoms of depression and anxiety have only been observed in the short-term, with very little evidence to suggest long-term impacts29.

The interventions included in the meta-analyses employed a variety of theories of change rather than all deriving from a single theoretical base, and theory was not assessed to see whether it influenced outcomes. This type of analysis does not really tell us much more than allowing us to make a broad claim that in general school-based psychosocial interventions produce positive effects on a range of student outcomes. It does not tell us whether interventions based on one theory of change are more effective in producing positive effects than others, and it does not help us parse out which component intervention techniques are causally related to changes in each target competency or specific outcomes. As we know, interventions which are explicitly theory-based produce stronger effects, allow for better assessment of effectiveness, facilitate our understanding of mechanisms of change, and therefore allow us to identify why and under what conditions an intervention may fail to produce the desired effects30. Simply stating that the SPHE curriculum is based on CASEL’s five competencies is not good enough. The NCCA needs to provide details on exactly which SEL programme they intend to utilise so that parents can evaluate the evidence to support its appropriateness and effectiveness. Further, I would like clarity around whether schools will be expected to systemically implement SEL so that it is woven into every aspect of students' education as CASEL recommends, whereby making it impossible for parents to withdraw their children from lessons on SEL.

The overall effectiveness of SEL interventions and whether they produce the desired outcomes, is largely dependent on implementation quality; that is, the degree to which a programme is delivered as intended31. When schools are surveyed, lack of teacher training is the most common barrier to quality implementation and a significant percent of teachers report not feeling well-equipped to educate students about mental health32. Evaluation of the MindOut SEL programme for 15-18 year olds in Ireland, found that only those schools that implemented the programme with high quality saw significant positive effects, with only one of those positive outcomes having been sustained at the 12-month follow up33. Do we really believe that we have enough time between now and the proposed introduction of the new curriculum in September to sufficiently train our teachers so that they feel competent enough to deliver the new curriculum to students effectively? I do not believe that a day or two of training is enough to prepare teachers to intervene on student's social and emotional wellbeing. Given that producing the desired positive effects is so heavily reliant on implementation quality, asking teachers to facilitate the new programme when ill-equipped to do so is a colossal waste of time and effort for all involved. Unless we can be certain that this programme will be delivered to a high enough quality to ensure that students will receive the promised positive effects, we will be doing them a huge disservice by taking time away from other core subjects and asking them to devote that time to a programme with uncertain returns. Finally, I would like to reiterate that any programme that uses SEL as a front for teaching Critical Social Justice, is inappropriate, voids any potential benefits, and is destabilising and detrimental to young people’s mental health. I am telling you in no uncertain terms, this type of programme has no place within our schools.

Conclusion

Taking all of this into account, the proposed changes to the curriculum should trigger alarm bells for parents and teachers alike. Parents, do not be fooled by the nice language and jargon used to dress the curriculum up as something other than what it is. Your child’s wellbeing is not what is paramount to advocates for critical pedagogy and SEL. They are not interested in equipping your children with the skills necessary to become competent individuals, able to succeed in the real world based on their own merit. Critical pedagogy is politically motivated and is interested only in shaping your children into individuals that will perform in service of radical political and societal transformation, surrendering themselves as individuals to a misguided collectivist vision. This educational movement, which is occurring at the same time across all western nations, is an assault on liberal democracy and our children are being indoctrinated into becoming its foot soldiers. Stand up for your children and do not allow them to be recruited into participating in the deconstruction of Irish society and culture as we know it. Teach your children that it is liberalism, not Critical Social Justice, that upholds the tenets of equality under the law and equality of opportunity for all, freedom of expression, respect for viewpoint diversity, and individual liberty. Teachers, if you were not aware prior to reading this letter what it was you were truly being asked to teach, please give serious consideration as to whether you are comfortable participating in this form of education. If not, I encourage you to stand up and refuse to implement the curriculum changes. To the NCCA and the Department of Education, you owe the people an explanation. I hope that you will adequately address every concern and question that I have raised within this letter, and I look forward to hearing your response.

Questions for Parents:

Do you believe that the responsibility for shaping your children’s dispositions and values should lie primarily with you and your family, as opposed to schools and educators?

Are you comfortable with your child being made to feel shame and guilt for their race/ethnicity, religion, sexuality, family culture, or socioeconomic status?

Are you comfortable with your children being led to believe that they are oppressors simply by virtue of their birth?

Do you send your children to school so that they can be influenced into adopting a Neo-Marxist ideology?

Are you happy for your children to base their worldview on sharply dividing people into oppressor vs. oppressed identity groups which are perpetually in conflict with each other?

Are you prepared to allow the Irish education system to adopt the same prejudiced views and teaching practices that have already infiltrated American, British, Canadian, and Australian schools?

Do you send your children to school so that they can learn to become activists?

Are you concerned that these practices may potentially increase mental health issues?

Are you comfortable with your children becoming less educated and more indoctrinated?

Do parents believe that childhood innocence is simply a social construct used to restrict children’s sexual exploration?

Do parents believe that teachers have enough specialised training to be intervening on their children’s psychological development?

Social, Personal, and Health Education/Relationships and Sexuality Education.

National Council for Curriculum and Assessment.

Much of the insights into critical pedagogy included here were derived from the work of James Lindsay, from his extensive essays and podcasts on New Discourses and his book The Marxification of Education.

Pluckrose, H., & Lindsay, J. (2020). Cynical Theories. Pitchstone Publishing.

See Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). What it means to be critical: Beyond rhetoric and toward action. In A. D. Reid, E. P. Hart, & M.A. Peters (Eds.), A Companion to Research in Education (pp. 259–261). Springer.

See Lewison, M., Flint, A. S., & Van Sluys, K. (2002). Taking on Critical Literacy: The Journey of Newcomers and Novices. Language Arts, 79(5), 382–392.

Kincheloe, J. L. (2008). Critical Pedagogy Primer (2nd ed.). Peter Lang.

See also Lynch, K. (2021).Education and Resistance to Injustices: Matters for Social Personal and Health Education (SPHE). Proceedings from the 4th SPHE Network Conference. https://sphenetwork.ie/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/conference_proceedings_2018.pdf

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Seabury Press.

Freire, P. (1985). The Politics of Education. Bergin & Garvey Publishers.

Freire, P. (1974). Conscientisation. Cross Currents, 24(1), p. 28.

Gottesman, I. (2016). The Critical Turn in Education: From Marxist Critique to Poststructuralist Feminism to Critical Theories of Race. Routledge.

See Marcuse, H. (1956). Repressive tolerance. In R. P. Wolff, B. Moore, Jr., & H. Marcuse (Eds.), A Critique of Pure Tolerance (pp. 81-123). Beacon Press.

See Curry-Stevens, A. (2007). New forms of transformative education: Pedagogy for the privileged. Journal of Transformative Education, 5(1), 33-58.

DiAngelo, R. (2018). White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism. Beacon Press.

Kendall, F. (2012). Understanding White Privilege: Creating Pathways to Authentic Relationships Across Race. Routledge.

See Applebaum, B. (2010). Being white, being good: White complicity, white moral responsibility, and social justice pedagogy. Lexington Books.

e.g. Bos, D. J., Dreyfuss, M., Tottenham, N., Hare, T.A., Galvan, A., Casey, B. J., & Jones, R. M. (2019). Distinct and similar patterns of emotional development in adolescents and young adults. Developmental Psychology, 00, 1-9.

Neary, A., & Rasmussen, M. L. (2019). Marriage equality time: Entanglements of sexual progress and childhood innocence in Irish primary schools. Sexualities, 0(0), 1-19.

Dyer, H. (2017). Queer futurity and childhood innocence: Beyond the injury of development. Global Studies of Childhood, 7(3), p. 293.

Pfeifer, J. H., Masten, C. L., Borofsky, L. A., Dapretto, M., Fuligni, A. J., & Lieberman, M. D. (2009). Neural correlates of direct and reflected self-appraisals in adolescents and adults: When social perspective-taking informs self-perception. Child Development, 80(4), 1016–1038.

Blakemore, S.-J., & Mills, K. L. (2014). Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 187–207.

Tamova, L., Andrews, J. L., & Blakemore, S.-J. (2021). The importance of belonging and the avoidance of social risk taking in adolescence. Developmental Review, 61, 100981.

Cohen, A. O., Breiner, K., Steinberg, L., Bonnie, R. J., Scott, E. S., Taylor-Thompson, K. A., Rudolph, M. D., Chein, J., Richeson, J. A., Heller, A. S., Silberman, M. R., Dellacro, D. V., Fair, D. R., Galvan, A., & Casey, B. J. (2016). When is an adolescent an adult? Assessing cognitive control in emotional and nonemotional contexts. Psychological Science, 27, 549-562.

Rosenberg, M. D., Casey, B. J., & Holmes, A. J. (2018). Prediction complements explanation in understanding the developing brain. Nature Communication, 9, 589.

Jagers, R. J., Rivas-Drake, D., & Borowski, T. (2018). Equity & social and emotional learning: A cultural analysis. CASEL. https://measuringsel.casel.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Frameworks-Equity.pdf

Jagers, R. J., Rivas-Drake, D., & Williams, B. (2019). Transformative social and emotional learning (SEL): Toward SEL in service of educational equity and excellence. Educational Psychologist, 54(3), 162-184.

Jagers, R., & Schlinger, M. (2020, June 12). SEL as a lever for equity and social justice [Webinar]. CASEL. https://casel.org/events/sel-as-a-lever-for-equity-and-social-justice/

Niemi, K. (2020, December 15). CASEL is updating the most widely recognized definition of social emotional learning. The74Million. https://www.the74million.org/article/niemi-casel-is-updating-the-most-widely-recognized-definition-of-social-emotional-learning-heres-why/

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Schellinger, K. B., Dymnicki, A. B., & Taylor, R. D. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405-432.

Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child Development, 88(4), 1156-1171.

Jagers, R. J., Skoog-Hoffman, A., Barthelus, B., & Schlund, J. (2021). Transformative social and emotional learning: In pursuit of educational equity and excellence. American Educator, 45(2), 12-17.

Saris, W., Revilla, M., Krosnick, J. A., & Shaeffer, E. (2010). Comparing questions with agree/disagree response options to questions with item-specific response options. Survey Research Methods, 4(1), 61-79.

Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child Development, 88(4), 1156-1171.

Clarke, A., Sorgenfrei, M., Mulcahy, J., Davie, P., Friedrich, C., & McBride, T. (2021). Adolescent Mental Health: A Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of School-Based Interventions. Early Intervention Foundation. https://www.eif.org.uk/files/pdf/adolescent-mental-health-report.pdf

Miche, S., & Prestwich, A. (2010). Are interventions theory-based? Development of a Theory Coding Scheme. Health Psychology, 29(1), 1-8.

Durlak, J. A. (2016). Programme implementation in social and emotional learning: Basic issues and research findings, Cambridge Journal of Education, 46(3), 333-345.

Durlak, J. A., & DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American journal of community psychology, 41(3-4), 327–350.

Byrne, M., Barry, M., & Sheridan, A. (2004). Implementation of a school-based mental health promotion programme in Ireland. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 6(2), 17-25.

Dowling, K., & Barry, M. (2021). Implementing school-based social and emotional learning programmes: Recommendations from research. Health Promotion Research Centre.

This is one of the most important documents in Ireland today. We simply cannot do nothing. Future generations are depending on us to safeguard their educational and societal intelligence. Really well researched and presented, well done all round.

Thank you so much. I will share widely