Like Lambs to the Slaughter

How the governemnt intends to sacrifice our babies and toddlers at the altar of social justice

This is a discussion of the literature review that was used to inform the updating of Ireland's early childhood curriculum. It concerns the corruption of the minds of our youngest, most innocent, and most vulnerable to manipulation. The literature review provides the academic argument for teaching our youngest children about critical race theory, critical social justice, and sustainable development (de-growth).

I have been researching the redevelopment of the curriculum for a number of years, yet nothing that I have read to date has disheartened me quite as much as the research that I have done into the updated Early Childhood Curriculum Framework, Aistear. It is now clear to me that not even our babies and toddlers will be able to escape the indoctrination that is happening in the Irish education system. The Aistear framework applies to all settings that care for children from birth to when they start primary school. The updated framework was informed by a literature review conducted by a team from DCU in 2022. Why was the original 2009 Framework updated and what changes have been made?

The NCCA tells us that Aistear was updated in order to “recognise and reflect societal changes, an increasingly qualified professional workforce, shifts in policy, and developments in research.”1 After reading the 2009 framework, it’s difficult to understand why it was viewed as insufficient in meeting the needs of young children as it appears to me, to already address all of the important aspects of early childhood development.

In addition to making changes to the core principles and how the aims of each theme are defined, the updated framework includes changes to the language used in an effort to be more “inclusive.” For instance, references to “he/she” have been changed to “they.” It is strangely no longer appropriate to say early childhood “practitioners.” They are now “educators.” A reference to “Parents” has been removed from the title of one of the core principles - “Parents, Family, and Community”. I would argue that this removal is a minor effort in a much larger agenda to shift away from the conventional view of parents as having the primary influence in shaping and educating their children.

A selection of notable differences between the 2009 and 2024 Aistear frameworks:

The most concerning changes found in the 2024 Aistear framework document is the emphasis on sustainable development and social justice, as well as the clear drive to create global citizens out of our children.

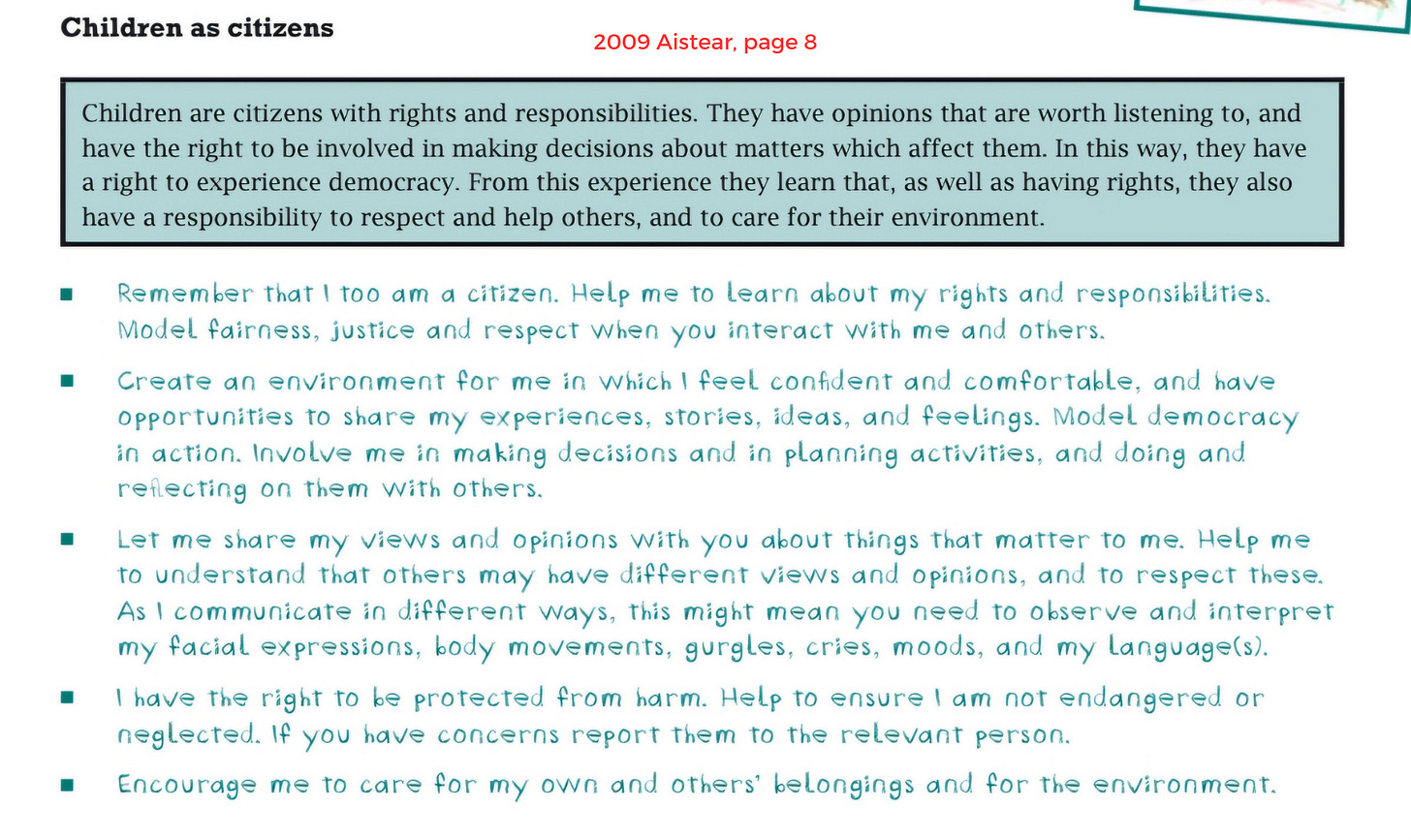

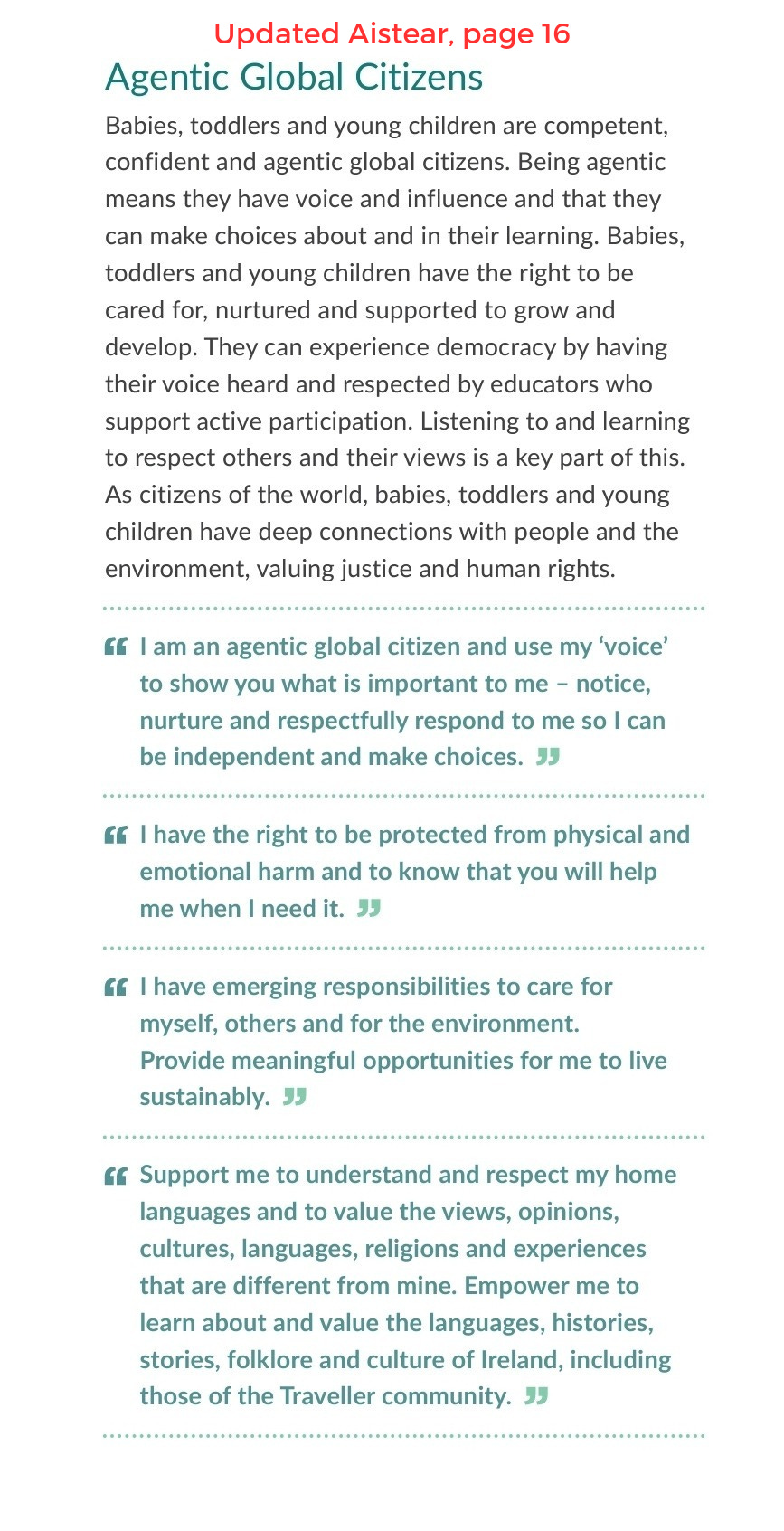

One of the principles included in the original framework was, “Children are citizens with rights and responsibilities.” Below is an excerpt of that principle as it appears in the 2009 document. I think most parents would agree that this is important and would view this description as adequately covering all the aspects of citizenship that are relevant to the age and developmental stage of babies and toddlers.

The updated Aistear framework, however, goes a step further than simply recognising children as citizens with rights and responsibilities. This principle now reads, “Babies, toddlers, and young children are competent, confident and agentic global citizens.” Further, the description references not just caring for the environment, but also living sustainably. Across the document, descriptions of each principle and the learning goals associated with the aims place distinctly less emphasis on the child as a developing individual in favour of emphasising themes of globalisation and collectivism. In what type of world is it necessary for babies and toddlers to be raised to see themselves as global citizens as opposed to simply citizens of Ireland?

A further update was made to the principle “Equality and Diversity”, which now reads as “Diversity, Equity and Inclusion” (DEI) within the new framework. As we all know, equality and equity are not the same thing. The 2009 framework already had a very progressive definition of equality, so this terminological shift seems unnecessary. If it were truly about simple fairness, as the document glossary indicates, then the prior use of equality should have been sufficient.

Dr Gillian Lake, who contributed to the literature review that informed these changes, states that the new framework asks that educators provide opportunities for children to engage with culture, languages, and “have experiences that are underpinned by social justice themes.”2 Why would babies and toddlers need to have experiences in playschool and creche that are underpinned by social justice themes?! What ever happened to providing a carefree childhood, where babies and toddlers are able to play and grow in an environment free from concerns that are beyond their ability to process or make sense of?

Small children lack the cognitive, emotional, and experiential tools needed to understand or contextualise global “social justice” issues. This is not a controversial statement. It’s a position backed by the corpus of literature in developmental psychology. Young children are concerned with their immediate environment and the important people with whom they have daily interactions. By forcing exposure to social justice issues which extend to the global scale, children are robbed of their innocence and ability to experience wonder, joy, and a sense of security. The world become a negative and threatening place, overwhelming their cognitive and emotional capabilities. Small children think in very concrete terms. Social justice, power imbalances, systemic oppression - these are highly abstract concepts which small children do not have the cognitive ability to make sense of. Introducing them to these very abstract societal concerns, which would require solutions that are too big for them to handle, threatens to stifle their budding sense of self-efficacy.

Let us turn to the literature review to get a better understanding of what is going on here. Firstly, I want to make clear that references to a social justice approach within Aistear documentation is not to be understood as simply teaching children to uphold the principles of fairness, equality and respect for the basic human rights of others. This can be done without adopting the propositions of critical theory. However, the literature cited within the literature review make it absolutely clear that they are referring to critical social justice. This definition of social justice is rooted in a critical theoretical approach, which views society as structured in such a way that inequality and oppression are embedded in the very fabric of society.3 Society is believed to be stratified along social group lines (race, gender, class, sexuality, ability etc.), with those in “dominant” groups (white, Christian, male, middle-class, able-bodied, heterosexual, cisgender) having access to unearned power and privilege, while “marginalised” groups are denied access. This inequality is believed to be reinforced both on the individual and structural level, with all of society being set up in such a way that provides unfair advantage to member of those dominant groups. From a critical social justice perspective, education is viewed as something that perpetuates and reproduces inequalities by reinforcing what are believed to be existing power structures which oppress individuals from “marginalised” groups. Social justice education, therefore, seeks to disrupt these power structures and redistribute power from dominant to marginalised groups (therefore creating equity). This is the theoretical lens through which they intend to teach our babies and toddlers.

What's important to recognise is that when social justice education is implemented, academic learning becomes only a secondary concern as every lesson becomes a means to an end to bring about social transformation. They don't care whether or not your kids learn or reach their academic and developmental milestones. They only care about socially engineering your children in order to shift their consciousness, values, and behaviours towards reflecting a specific ideological worldview.

A closer look at the literature review:

Anti-bias education and the accentuation of race

One of the themes of Aistear is “Identity and Belonging.” Discussion of this theme within the literature review makes reference to the fact that “Ireland is an increasingly diverse society” (pg. 51) and that educational provision must adapt in response to our new “superdiverse” nation (pg. 137). As such, the review suggests that early childhood practitioners should adopt anti-bias goals, which centre on 4 themes - identity, diversity, justice, and activism (pg. 52). These goals and their descriptions are lifted from the work of authors Louise Derman-Sparks and Julie Olsen Edwards. Their paper, The goals of anti-bias education: Clearing up some key misconceptions4 is cited in reference to the recommendation to adopt these goals within Aistear. The work of Derman-Sparks is also cited extensively throughout the literature review.

Derman-Sparks and Edwards define the identity goal as, “Each child will demonstrate self-awareness, confidence, family pride, and positive social/group identities.” On the surface this sounds acceptable, but it is within the authors discussion of this goal that we are able to see what they truly mean, and it’s rather twisted. The authors state that teachers sometimes bypass this goal when working with white children because they assume that white children do not need guidance in developing a positive racial identity. The authors do not go on to say, as you might first assume, that white children should be taught in the same manner as children from other races and encouraged to develop a healthy appreciation for their background, while positively embracing their cultural heritage. No. According to the authors, white children developing a positive racial identity entails helping them to “resist internalizing the racist messages of white superiority” (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2017, pg 15). The authors further go on to discuss how children of colour can also absorb prejudices against other groups of colour, yet no mention is made of potential prejudices against white children. This reflects the absurdly false belief among proponents of CRT that it is impossible to be racist toward white people because white people are believed to be the oppressor class. This position also perpetuates the false belief that all white people are inherently racist or prejudiced. These are not messages that I want my very little children to internalise about themselves. Teaching small children that there is something inherently flawed about them (i.e., their race, the colour of their skin) produces feelings of toxic shame and is a form of emotional abuse.

Over a year after Norma Foley and the head of the NCCA, Arlene Forster were called out for including the concept of white privilege in the draft SPHE specification,5 here it is again cropping up in our early years curriculum recommendations. The NCCA and Department of Education seem hell bent on teaching white Irish children to be ashamed of themselves. Although overt references to white privilege in specification documentation have since been carefully avoided, the concept is alive and well within the curriculum. They have provided an open door for teachers to run with these concepts in the classroom because the groundwork and justification to do so has been made in supporting curricular documents (such as this literature review).6

Throughout the section on identity, there is a clear call for educators to make race a salient factor for babies and toddlers. For instance, the authors of the literature review state that babies should be exposed to opportunities to notice and name racial differences, “My skin is black; yours is white” (pg. 52). Further, they state that providing children with these experiences helps them to develop the “skills to act with others or alone against prejudice and discriminatory actions.” But increasing awareness of racial differences tends to correspondingly increase prejudice and discrimination, creating more divided and hostile environments. This should be evident to anyone who has been paying attention over the last decade or so as DEI initiatives were implemented across all aspects of society. Race relations have gotten worse, not better. And we have research that backs that up now.7 DEI increases hostility between identity groups, leads to the perception of prejudice in situations where it doesn’t actually exist, and leads to greater agreement with extreme authoritarian rhetoric. Why would we move towards embedding DEI into how we teach our youngest when we have already seen the dire consequences of it across all other areas of society? The answer to failed DEI is not to push even more DEI.

Culturally responsive pedagogy

The authors of the literature review also recommend a shift to multicultural educational approaches such as culturally competent or culturally sustaining approaches. Further, they urge against “superficial and simplistic inclusion of minority figures or cultures without recognising the power differentials” (pg. 53). These educational approaches are essentially critical race theory repackaged. For proponents of such education, power is central to understanding and analysing everything, and it is not simply enough to include stories or teachings about minority cultures within the classroom. An emphasis must be placed on power struggles between racial groups, where some groups are framed as unavoidably oppressed and others oppressors. This approach to education is about redistributing narrative power and who gets to define truth, what is considered knowledge, and ensuring that “power” is passed to the “marginalised” groups. The obsession that these people have with power is a reflection, not of real power differentials, but of their own thirst to possess and wield power against those that they are prejudiced against.

Culturally responsive teaching primes students to interpret everything through the lens of critical race theory, whereby students learn to believe that power dynamics impact the racialised identities of themselves and others at all times and in all circumstances. They are taught to use their outrage and sense of unfairness about this to “dismantle systemic racism.” Consistent with this, the literature review states that children should be supported to “challenge unfairness and exclusionary behaviours to interrupt cycles of oppression” (pg. 141). Again, keep in mind, we are talking about babies and toddlers here. Small children are ego-centric and therefore, their sense of fairness is focused on when they have received unfair treatment (e.g., when another child gets more than them, someone has taken something of theirs, their turn has been skipped). Abstract fairness, for instance between others apart from themselves or among groups of people, is largely beyond their cognitive, social and developmental stage. Further, the idea that they are acting in ways that challenge unfairness in order to “interrupt cycles of oppression” would require the capacity for abstract and second-order reasoning, which they most certainly do not possess at that age.

Leading author in the field, Gloria Ladson-Billings states that one of the goals of this form of teaching is to help students to “develop a critical consciousness through which they challenge the status quo of the current social order.”8 If this sounds like critical pedagogy to you, that's because Ladson-Billings was greatly influenced by the work of Paulo Freire. However, she specifically applies his approach to “liberating” racial minorities. As such, the focus of this form of teaching is always on minority students, while white students must learn to “de-centre” themselves in the classroom.

Although culturally responsive teaching was marketed as improving academic success and creating more equitable outcomes for students (i.e., closing the achievement gap), proponents have failed to prove that it achieves this. As explained in one of the papers cited in the Aistear literature review, most studies investigating this form of instruction fail to document relevant outcomes in such a way that allows for effectiveness to be evaluated.9 But we can simply look, for instance, at literacy statistics for children in the US where culturally responsive teaching has become widespread in public schools. Almost two-thirds of students are unable to read at grade level and reading proficiency continues to decline with each passing year.10 In their defence, these educational quacks claim that it is about the process rather than outcomes. I disagree. Outcomes are important, and if what you are doing as a teacher is ineffective in producing the desired academic and developmental outcomes, then it doesn't belong in the classroom. For the NCCA to adopt this into Irish education tells me that they are more interested in investing in the latest “politically correct” educational fad than ensuring that Irish children are properly educated. While the top brass in the NCCA pat themselves on the backs for being oh so progressive, our children are having the joy of their early years and their education stolen from them.

Social and emotional learning

The literature review also highlights a need to place explicit focus on social and emotional learning (SEL) in early childhood and cites CASEL as a source. I have previously written about CASEL's SEL within an open letter regarding the review of the Junior Cycle Wellbeing curriculum and critiqued the validity of their claims in relation to student outcomes, which can be found here. I echo those same concerns here in relation to including SEL within the ECEC curriculum.

The introduction of social and emotional learning at such a young age fits with the curriculums emphasis on sustainable development. In 2019, UNESCO published an article in their publication The Blue Dot, titled SEL for SDGs: Why social and emotional learning is necessary to achieve the sustainable development goals.11 In the article, the authors argue that working towards achieving some of the SDGs may require certain trade-offs. Trade-offs that may for example, compromise personal wellbeing. They go on to argue that this conflict between the self (regulation and preservation) and the collective (achievement of the SDGs) will produce cognitive dissonance, ultimately discouraging individuals from engaging in sustained action in pursuit of the SDGs. They propose that the solution to this problem is to use social and emotional learning in schools in order to shape children so that they are inclined to place the “collective good” over their individual interests and self-preservation. In other words, from infancy, they want to use psychological intervention to manipulate our children into developing the dispositions and values which ensure that they will be good and compliant comrades, always ready to sacrifice the self for the collective. As the literature review states, teaching children compassion as a socio-emotional competency is key to empowering them as “global citizens to lead sustainable lifestyles that support and sustain collective wellbeing” (pg. 102). Notice that they don’t talk about compassion in the universal sense - as the ability to understand and share the feelings of others and being moved to act with kindness. The competency has been filtered through their own ideological lens and the intention is to teach it in such a way that serves their own purposes.

Sustainability

The authors of the literature review call for moving beyond education for sustainability as mere environmentalism, to “create the potential for transformative practice” (pg. 150). Further, they encourage approaches to teaching about sustainability that focus on how children can become, both individually and collectively, agents of change for sustainable development. Whenever I see references to transformative practices and agents of change my alarms bells go. This is coded language for education that attempts to socially engineer children into becoming social justice activists. Children will be taught to wholesale adopt a set of beliefs and talking points about an issue, discouraged from engaging in genuine critical thinking, and pushed to engage in radical activism without considering the consequences of their actions or whether what they are doing has any benefits to the cause aside from creating disruption. This is all well beyond the early years so it's baffling to see it discussed in relation to the early years curriculum. When did it become acceptable to place the weight of the world on the shoulders of our innocent little ones who need and deserve a childhood characterised by stability and safety in order to thrive?

It’s important to note that the literature review is invoking a conceptualisation of sustainability which does not simply refer to environmental sustainability, but one that also includes economic and social dimensions (pg. 218). Sustainable development is a bait and switch. When most people think about what is appropriate for their small children to be taught about sustainability, they imagine things like teaching them how to care for the environment, have an appreciation for the natural world, and to not be wasteful. However, a conceptualisation of sustainability that includes economic and social sustainability requires a complete overhaul of the current social order, including the equitable (re)distribution of resources and social outcomes. In other words, socialism.12 What is being proposed here, is for our children to be taught from infancy to not just accept, but also to call for degrowth under socialism.

Where is this coming from?

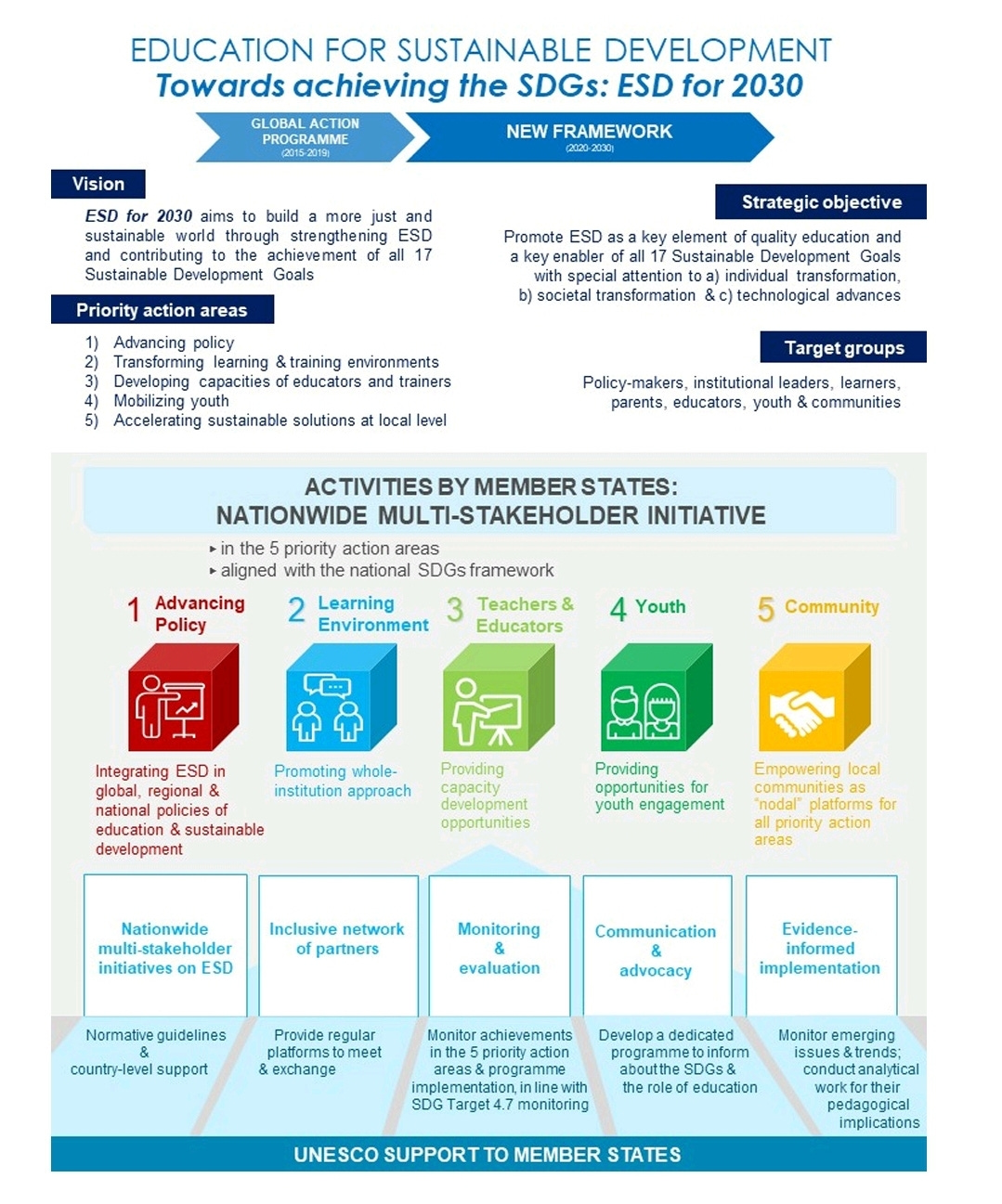

Connecting the content changes in the specification to policy documents, reveals that the updating of the Aistear framework has largely been about meeting Ireland’s commitments to the United Nation’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In particular, Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4: Ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education. Within SDG 4, Target 4.7 specifically outlines the requirement for member states to ensure the implementation of education for sustainable development (ESD), which embeds concepts such as sustainable consumption, global citizenship, cultural diversity, climate change, and social justice into teaching practices and curricula.

UNESCO’s Education for Sustainable Development: Towards achieving the SDGs roadmap asks countries to incorporate ESD into 5 action areas.13 They are:

Advancing Policy: ESD must be integrated into national policies and strategies on education, climate action, and economic development.

Transforming Learning Environments: All education and training settings should adopt a whole-institution approach to ESD. All institutions should have their own strategic policies and measures which reinforce their commitment to ESD. And finally, ESD themes should be integrated into the curriculum at all levels, from early childhood to higher education and lifelong learning.

Building Teacher and Educator Capacities: Countries must invest in providing opportunities for continuing professional development in ESD for teachers and it is to be included in initial teacher training.

Empowering Youth: Young people are viewed as critical agents of change for achieving the sustainable development goals and key drivers of systemic change.

Mobilising Communities: Mobilise local communities to participate in achieving the SDGs by fostering “grassroots engagement”. (Although it's hard to see how community initiatives could be considered grassroots if they are instigated at the governmental level at the behest of the UN)

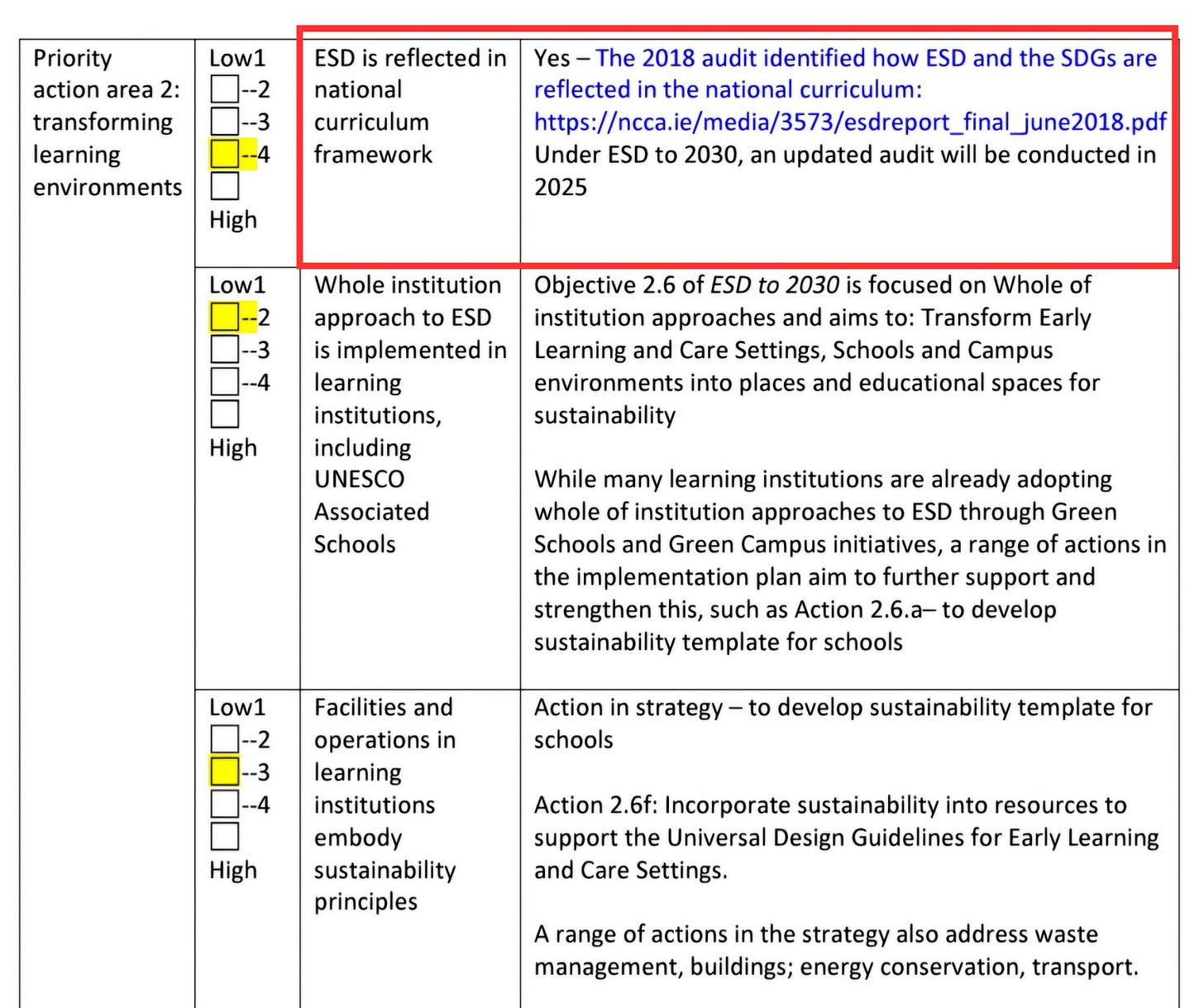

As you can see, it is a part of this roadmap to embed ESD into all levels of education, including early childhood. Member states must monitor and evaluate their progress on these action areas and submit periodic progress reports to UNESCO. Ireland’s initiative on Education for Sustainable Development can be found here. Within this document, we can see that in 2018, the NCCA conducted an audit to identify how ESD and the SDGs were reflected in the national curriculum. There has clearly been a great push to have all curriculum areas updated before the next audit in 2025.

What is happening with the curriculum is not occurring organically. It is not a product of grassroots calls for these changes or advancements in research. The direction of the redevelopment of the curriculum is very much contrived and has been top-down initiated. Education is the weapon being used to totally restructure society. A generation from now, we will not have independent and innovative thinkers emerging from Irish schooling. We will have ideologically uniform robots, incapable of independent thought or true critical analysis. Our youth will not have the foundational academic or psychological skills needed to become competent and functioning adults. They will be dependent on a nanny state and willingly calling for their own enslavement by an authoritarian global government because they have been taught to subjugate themselves to the collective.

The younger that this indoctrination begins, the greater the damage that will be done, and the longer it will take to unravel the psychological grip of this cult-like group-think. Infancy and toddlerhood is when our brains are most malleable and when we begin to form our core beliefs about the world. By starting the indoctrination in early years, this ensures that this worldview becomes each child’s foundational framework. The set of beliefs included within this worldview are not simply adopted, as would happen when a person is indoctrinated later in life. This worldview’s distorted beliefs about trust, authority, and the nature of reality become wired in as neural defaults, and therefore are indistinguishable from the child's sense of self and identity. The child has known nothing different. To “de-programme” a child from this level of indoctrination is infinitely more difficult because it requires the child dismantle everything that they know.

Despite the fact that the above educational approaches are often presented as noble efforts to create a more just and fair world, and as a solution to the current social ills, the real outcomes that are produced are far from positive. Think for a second about what the consequences will be for children, and society as a whole, if they are raised from infancy to see every interaction between people as a contest for dominance and power. This is what this form of education teaches. It is based on conflict theory, which views society as an inherently unequal battleground, where (social) groups are in a constant state of conflict with each other as they vie for scarce resources. If children base the foundations of their worldview on this belief, they learn early on to have a deep seated mistrust of others. They will develop a hostile attribution bias, where they perceive even benign behaviours of certain groups as threatening and intentionally oppressive.

Teaching children that the world is characterised by invisible and inescapable systems of domination creates fertile breeding ground for hopelessness and cynicism. Teaching them that they must become active citizens or agents of change to counter existential threats like climate disaster or the systemic oppression of certain groups, places the responsibility for solving overwhelmingly large problems on their shoulders, leading to anxiety and a sense of chronic instability. We constantly hear about the need to raise resilient children but this will produce the opposite. Kids need exposure to age-appropriate struggles in order to develop resiliency. When you ask them to confront struggles they’re not equipped to handle you break down their confidence, erode their sense of self-efficacy, and overwhelm their coping mechanisms. They do not learn to regulate their emotions in incremental and manageable ways. This is particularly important for those early developmental years when they’re building the neural scaffolding associated with emotion and control, which will impact their ability to manage their feelings for the rest of their lives.

What is happening in Irish education is ideological grooming. Imposed on our children by the NCCA, at the behest of the United Nations. The NCCA has been working diligently over the last number of years to completely overhaul the curriculum and infuse it with their ideology at every single level, from early years up to senior cycle. They’ve packaged it and presented it to the public as wonderful progress. They have lied to us and told us that this is all the result of extensive consultation with stakeholders and parents but we can see that it is actually the result of committments they have made to international bodies. They have ignored parent’s concerns and ploughed on with their plans. They have handed over the reins to radical ideologues from Ireland’s universities. Just take a look at the co-opted members of each curriculum area working group and their academic profiles. You will find ideological conformity - every one of them are experts in critical pedagogy, social justice, sustainability, global citizenship education, critical studies, and development education. There is an obvious agenda here and it’s time parents and teachers alike put a stop to their attempts to weaponize our children as tools for social transformation. It is wrong at all levels of education, but particularly egregious when they target babies and toddlers.

NCCA, Draft Updated Aistear: the Early Childhood Curriculum Framework For Consultation. https://ncca.ie/media/6362/draftupdatedaistear_for-consultation.pdf

https://childpaths.ie/2024/10/17/updating-aistear-what-can-early-childhood-educators-expect-regarding-their-practice/#:~:text=The%20National%20Council%20for%20Curriculum,be%20launched%20in%20October%202024.

Sensoy, O., & DiAngelo, R. (2017). Is everyone really equal? An introduction to key concepts in social justice education. Teachers College, Columbia University.

https://antibiasleadersece.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Goals-of-ABEMisconceptions.pdf

https://gript.ie/white-irish-privilege-references-removed-from-sphe-curriculum/

Excerpt below this citation taken from:

Towards an overview of a Redeveloped Primary School Curriculum: Learning from the past, learning from others Dr. Thomas Walsh, National University of Ireland, Maynooth.

https://ncca.ie/media/4426/towards-an-overview-of-a-redeveloped-primary-school-curriculum-learning-from-the-past-learning-from-others.pdf

https://networkcontagion.us/reports/instructing-animosity-how-dei-pedagogy-produces-the-hostile-attribution-bias/

https://www.nationalreview.com/news/dei-training-increases-perception-of-non-existent-prejudice-agreement-with-hitler-rhetoric-study-finds/

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). But that's just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory into Practice, 34(3), 159-165.

Kelly et al. (2021). What is culturally informed literacy instruction? A review of research in P-5 contexts. Journal of Literacy Research, 53(1), 75-99.

https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/data/

https://mgiep.unesco.org/article/sel-for-sdgs-why-social-and-emotional-learning-is-necessary-to-achieve-the-sustainable-development-goals

https://monthlyreview.org/2023/07/01/planned-degrowth/

https://newdiscourses.com/2021/10/sustainability-tyranny-21st-century/

UNESCO, Framework for the Implementation of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) Beyond 2019. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000370215

Remarkably well researched and written paper. Assume you’ve read and listened to James Lindsay on this?

Excellent research and very chilling stuff. There is a national curriculum review going on in the UK and this forewarns us of what is to in all probability be brought in here too.

Have cross posted.

https://dustymasterson.substack.com/p/the-search-for-one-man

Dusty